Catalog 171

All books are first printings of first editions or first American editions unless otherwise noted.

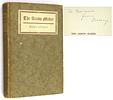

NY, Duffield and Co., 1911. "A drama in three acts" dealing with Indian life, by the author of The Land of Little Rain, which helped establish Austin not only as an early American nature writer but also as a pioneering feminist, whose study of the desert and desert cultures was tinged with political consciousness and insight. She eventually moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and became part of the literary and artistic circle cultivated by Mabel Dodge, whose other friends included such luminaries as Ansel Adams and Georgia O'Keeffe. Austin was working on her collaboration with Adams -- the limited edition Taos Pueblo -- in 1929, the year that Adams met Georgia O'Keeffe, who was in Santa Fe for the summer to paint, and Adams and O'Keeffe became lifelong friends. This copy is inscribed by Austin "To Georgia from Mary" -- although we cannot confirm that it is inscribed to O'Keeffe. Light wear to the spine extremities and joints, with tanning to the spine label; still a near fine copy.

[#033900]

SOLD

NY, Duffield and Co., 1911. "A drama in three acts" dealing with Indian life, by the author of The Land of Little Rain, which helped establish Austin not only as an early American nature writer but also as a pioneering feminist, whose study of the desert and desert cultures was tinged with political consciousness and insight. She eventually moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and became part of the literary and artistic circle cultivated by Mabel Dodge, whose other friends included such luminaries as Ansel Adams and Georgia O'Keeffe. Austin was working on her collaboration with Adams -- the limited edition Taos Pueblo -- in 1929, the year that Adams met Georgia O'Keeffe, who was in Santa Fe for the summer to paint, and Adams and O'Keeffe became lifelong friends. This copy is inscribed by Austin "To Georgia from Mary" -- although we cannot confirm that it is inscribed to O'Keeffe. Light wear to the spine extremities and joints, with tanning to the spine label; still a near fine copy.

[#033900]

SOLD

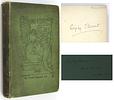

London, The Fabian Society, 1889. Inscribed by contributor Annie Besant to her son, (Arthur) Digby Besant (twice) in April, 1890. With Digby Besant's ownership signature and bookplate. The volume was edited by George Bernard Shaw. Besant's contribution is titled "Industry Under Socialism." Besant was a socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, and an early supporter of, and speaker for, the Fabian Society. In 1890, the year she gave her son this book, she met Helena Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society; after Blavatsky's death in 1891, Besant became one of the leaders and key figures in the theosophical movement, which eventually split into several factions, and also led to the Anthroposophy movement, when Rudolph Steiner, another leader in the Theosophical Society, broke away from it. Spine and covers darkened, with wear to the joints; a good copy, and a unique family association copy. Books signed by Besant, one of the most prominent female activists of the 19th and early 20th centuries, are uncommon.

[#033604]

SOLD

London, The Fabian Society, 1889. Inscribed by contributor Annie Besant to her son, (Arthur) Digby Besant (twice) in April, 1890. With Digby Besant's ownership signature and bookplate. The volume was edited by George Bernard Shaw. Besant's contribution is titled "Industry Under Socialism." Besant was a socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, and an early supporter of, and speaker for, the Fabian Society. In 1890, the year she gave her son this book, she met Helena Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society; after Blavatsky's death in 1891, Besant became one of the leaders and key figures in the theosophical movement, which eventually split into several factions, and also led to the Anthroposophy movement, when Rudolph Steiner, another leader in the Theosophical Society, broke away from it. Spine and covers darkened, with wear to the joints; a good copy, and a unique family association copy. Books signed by Besant, one of the most prominent female activists of the 19th and early 20th centuries, are uncommon.

[#033604]

SOLD

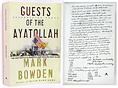

NY, Atlantic Monthly, (2006). The advance reading copy of Bowden's book on the Iranian hostage crisis. This copy was used for review by author Philip Caputo, for Publisher's Weekly, and bears his highlighting and turned page corners, as well as 1-1/2 pages of draft text written on the recto and verso of the first blank. Covers splayed; very good in wrappers.

[#033932]

$175

NY, Atlantic Monthly, (2006). The advance reading copy of Bowden's book on the Iranian hostage crisis. This copy was used for review by author Philip Caputo, for Publisher's Weekly, and bears his highlighting and turned page corners, as well as 1-1/2 pages of draft text written on the recto and verso of the first blank. Covers splayed; very good in wrappers.

[#033932]

$175

[ca 1950s]. An album containing early photographs by and of William S. Burroughs and other figures of the Beat generation, including photo collages and partial collages, with annotations by Burroughs; a photobooth portrait; a passport photo; a negative of an unpublished Brion Gysin photograph of Burroughs from 1959 (with contemporary archival print); and other images. 32 photographs in all, plus calling cards of Bruno Heinrich and Charles Henri Ford, and a copy of Driffs magazine -- "The Antiquarian and Second Hand Book Fortnightly" -- which includes Part 1 of Iain Sinclair's "Definitive Catalogue" of the Beats -- this part being devoted entirely to the works of William Burroughs, with this album as item number 80 in the catalogue.

[ca 1950s]. An album containing early photographs by and of William S. Burroughs and other figures of the Beat generation, including photo collages and partial collages, with annotations by Burroughs; a photobooth portrait; a passport photo; a negative of an unpublished Brion Gysin photograph of Burroughs from 1959 (with contemporary archival print); and other images. 32 photographs in all, plus calling cards of Bruno Heinrich and Charles Henri Ford, and a copy of Driffs magazine -- "The Antiquarian and Second Hand Book Fortnightly" -- which includes Part 1 of Iain Sinclair's "Definitive Catalogue" of the Beats -- this part being devoted entirely to the works of William Burroughs, with this album as item number 80 in the catalogue. The photographs are primarily from the early 1950s -- the ones annotated by Burroughs having dates from 1952 to 1954. Several photographs are taped together, forming early visual collages, while a number of the individual photos have sellotape along their edges, suggesting they were at one time part of a larger collage. The collages, or collage fragments, represent some of Burroughs' earliest attempts to use visual images in the way he was using words -- to transcend time and space, and link together various aspects of his life and world, in ways that correlate to a "mindscape" -- akin to the connections between the stories he wrote during that period that were collectively known as the Interzone, which was also an early title for Naked Lunch.

Brion Gysin, in his 1964 essay, 'Cut ups: A Project for Disastrous Success,' wrote that "Burroughs was more intent on Scotch-taping his photos together into one great continuum on the wall, where scenes faded and slipped into one another, than occupied with editing the monster manuscript" -- i.e., Naked Lunch, aka his Word Hoard. And Burroughs wrote in one of his Adding Machine essays: "I was back in my old garden room at the Villa Muniria [in Tangier], and it was here that I first started making photo-montages." This was March 1961.

The provenance of this group of materials is "the legendary Hardiment suitcase," belonging to poet Melville Hardiment, a friend of Burroughs during the years 1960-62, who is also known as the first person to have given Burroughs LSD, apparently without Burroughs' advance knowledge. Hardiment's wife at the time was Harriet Crowder, a photographer who is well-known for having taken the portrait of Burroughs on the LP "Call Me Burroughs." Hardiment bought a number of items from Burroughs in that time period and famously kept them in a suitcase. According to his second wife, Pat Hardiment, Melville would sell off the contents bit by bit, when he needed money. One group of materials ended up at the University of Kansas, and is known there as the Burroughs-Hardiment Collection: this group went from Hardiment to the bookseller Pat Zanelli, to bookseller Larry Wallrich, and then to the university.

A second group of photographs and collages went into the collection of photographer Richard Lorenz, and were exhibited in the 1996 show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art -- "Ports of Entry: William S. Burroughs and the Arts." By 1996, Burroughs' influence on the visual arts was sufficiently deep and widespread to justify a museum show of its own. The photos and collages in the Lorenz collection were of the same subjects, from the same time period, with the same annotations as the Kansas photos, and would appear to have also come from Hardiment's suitcase. Several of the Lorenz images remain taped together forming collages, or mini-collages; many others, though, now stand alone, although by the evidence they were once part of a larger construct.

This third group, offered here, went from Hardiment to Iain Sinclair, likely again via Pat Zanelli (Sinclair recalls buying the lot from a woman bookseller, and Zanelli is the most likely candidate). Like the photos in Kansas and those in the Lorenz collection, many of these have sellotape on the edges, and like the collages in the Lorenz collection, some are still taped together, forming collages themselves or representing collage fragments.

Tape shadows on the versos of some of the images both here and at the University of Kansas hint that Burroughs may have created the collages and then, when he began experimenting with the cut-up technique in writing, have cut-up the collages with the intent of applying this same technique to visual imagery. The Lorenz items were not presently available for examination of their versos, but some evidence supports this notion, such as that some of the images in the collages were partially torn away, and that there was evidence of the collages having been part of a larger grouping previously.

William S. Burroughs is known as a key figure of the literary avant garde of the 20th century, and the impact of his work on the visual arts -- both his own artwork and others' works derived from his literary writings -- was sufficient to justify a major museum show and catalog. These snapshots and snapshot collages represent some of his earliest efforts to explore the ideas he was working on in his writing using visual materials. Isaac Gewirtz, the curator of the Burroughs archive in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, wrote in his book on Burroughs, Beatific Soul, that the Interzone was an "imaginary city" which was "a combination of New York, Mexico City, and Tangier" in which Burroughs "construct[ed] hallucinatory, interconnected narratives for its numerous characters." These groups of photographs show Burroughs venturing even farther afield and including "Tetuan" [i.e., Tetouan], in Morocco; Huanuco, in Peru; and Paris, as part of his interzone, or mindscape. The Huanuco photographs and a Pucallpa, Peru calling card date from Burroughs' trip to South American to meet with Harvard ethno-botanist Richard Evans Schultes (aka "Dr. Schindler" in The Yage Letters) to try ayahuasca for the first time.

Early, seminal material from William S. Burroughs, an icon of the Beat Generation, whom Norman Mailer, in 1962, called "the only American novelist living today who may conceivably be possessed by genius."

[#033847] $24,900 (Brighton), Unicorn, 1971. Clothbound first edition limited to 99 numbered and signed copies, this being one of only 9 hors commerce copies and inscribed by the author to Claude Pelieu and Mary Beach, friends and collaborators with Burroughs on a number of different projects, mostly in the mid-1960s. The inscription reads: "For Claude and Mary/ all the best at/ Christmas/ William Burroughs." One of Burroughs' smallest limitation for the entire edition, the hors commerce copies are exceedingly scarce: we could find no record of one ever turning up at auction; and, while nearly 50 copies of this edition are housed in research libraries, we could find no evidence that any of them were hors commerce copies or that any of them had a similarly rich association. Even the Carter Burden copy, at the Morgan Library, is one of the copies that was for sale, numbered 1-90, and Burden made an effort -- usually successful -- to get every variant he could of the titles and authors he collected. Brown cloth without dust jacket, as issued. A few faint spots to the cloth; near fine. Originally issued with a 12" LP record, not present here and not present with most of the copies that have been on the market or are in institutional collections: many of the LPs were damaged prior to publication, and books were issued without the accompanying record. It is not known if the hors commerce copies would have been accompanied by the LPs or not, but it is reasonable to surmise that the few surviving LPs would have been placed with copies that were to be sold in the trade, not with those held back from commerce. An excellent association copy between key figures of the Beat generation and counterculture, and an extremely scarce issue of an uncommon Burroughs title.

[#033848]

SOLD

(Brighton), Unicorn, 1971. Clothbound first edition limited to 99 numbered and signed copies, this being one of only 9 hors commerce copies and inscribed by the author to Claude Pelieu and Mary Beach, friends and collaborators with Burroughs on a number of different projects, mostly in the mid-1960s. The inscription reads: "For Claude and Mary/ all the best at/ Christmas/ William Burroughs." One of Burroughs' smallest limitation for the entire edition, the hors commerce copies are exceedingly scarce: we could find no record of one ever turning up at auction; and, while nearly 50 copies of this edition are housed in research libraries, we could find no evidence that any of them were hors commerce copies or that any of them had a similarly rich association. Even the Carter Burden copy, at the Morgan Library, is one of the copies that was for sale, numbered 1-90, and Burden made an effort -- usually successful -- to get every variant he could of the titles and authors he collected. Brown cloth without dust jacket, as issued. A few faint spots to the cloth; near fine. Originally issued with a 12" LP record, not present here and not present with most of the copies that have been on the market or are in institutional collections: many of the LPs were damaged prior to publication, and books were issued without the accompanying record. It is not known if the hors commerce copies would have been accompanied by the LPs or not, but it is reasonable to surmise that the few surviving LPs would have been placed with copies that were to be sold in the trade, not with those held back from commerce. An excellent association copy between key figures of the Beat generation and counterculture, and an extremely scarce issue of an uncommon Burroughs title.

[#033848]

SOLD

NY, Henry Holt, (1992). The uncorrected proof copy of Butler's Pulitzer Prize-winning collection of stories, many of them dealing with the Vietnam war and its aftermath. From the library of Philip Caputo, and with several passages highlighted by him: the published book featured a blurb by Caputo on the jacket's front flap. Scarce, even without the association. Some light soiling to covers; near fine in wrappers.

[#033933]

SOLD

NY, Henry Holt, (1992). The uncorrected proof copy of Butler's Pulitzer Prize-winning collection of stories, many of them dealing with the Vietnam war and its aftermath. From the library of Philip Caputo, and with several passages highlighted by him: the published book featured a blurb by Caputo on the jacket's front flap. Scarce, even without the association. Some light soiling to covers; near fine in wrappers.

[#033933]

SOLD

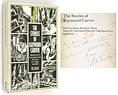

(London), Picador/Pan, (1985). Inscribed by Carver to Robert Stone: "For Bob - with admiration and good wishes always. With love and in friendship -- Ray. July 22. Port Angeles!" This was the first publication in Great Britain of Carver's collected fiction, this being a volume with no U.S. equivalent, and including all three of his major collections: Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?; What We Talk About When We Talk About Love; and Cathedral. Uncommon signed, and an excellent personal and literary association copy: Stone visited Carver in Port Angeles, Washington, and the two got on well, went fishing together, and generally found a quick and easy rapport. Stone won the National Book Award for his second novel, Dog Soldiers, in 1975; Carver's first collection -- Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? -- was a National Book Award finalist in 1977, and his influence on the American short story continued until his death in 1988. Only issued in wrappers. Age-toned, foxed, and spine-creased; about very good.

[#033666]

SOLD

(London), Picador/Pan, (1985). Inscribed by Carver to Robert Stone: "For Bob - with admiration and good wishes always. With love and in friendship -- Ray. July 22. Port Angeles!" This was the first publication in Great Britain of Carver's collected fiction, this being a volume with no U.S. equivalent, and including all three of his major collections: Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?; What We Talk About When We Talk About Love; and Cathedral. Uncommon signed, and an excellent personal and literary association copy: Stone visited Carver in Port Angeles, Washington, and the two got on well, went fishing together, and generally found a quick and easy rapport. Stone won the National Book Award for his second novel, Dog Soldiers, in 1975; Carver's first collection -- Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? -- was a National Book Award finalist in 1977, and his influence on the American short story continued until his death in 1988. Only issued in wrappers. Age-toned, foxed, and spine-creased; about very good.

[#033666]

SOLD

NY, Random House, (1985). Inscribed by Carver to Robert Stone: "For Bob, with hopes you'll find some of these to your liking. With love, Ray. Port Angeles. July 22, 1985." A collection of poetry. Mild foxing; near fine in a very good, partially faded dust jacket with one short edge tear and a creased front flap. A good association copy.

[#033665]

$1,500

NY, Random House, (1985). Inscribed by Carver to Robert Stone: "For Bob, with hopes you'll find some of these to your liking. With love, Ray. Port Angeles. July 22, 1985." A collection of poetry. Mild foxing; near fine in a very good, partially faded dust jacket with one short edge tear and a creased front flap. A good association copy.

[#033665]

$1,500

(Somerville), Candlewick Press, (2017). The advance reading copy of Bartok's Dickensian, steampunk middle grade fantasy about orphaned "groundlings," which even before publication was slated to be both a movie and a Broadway musical. Signed by the author. Textual differences exist between this advance copy and the finished book. Light tap to spine crown, else fine in wrappers. Bartok won the National Book Critics Circle Award for her memoir The Memory Palace. Uncommon as an advance copy, and especially so signed.

[#034438]

SOLD

(Somerville), Candlewick Press, (2017). The advance reading copy of Bartok's Dickensian, steampunk middle grade fantasy about orphaned "groundlings," which even before publication was slated to be both a movie and a Broadway musical. Signed by the author. Textual differences exist between this advance copy and the finished book. Light tap to spine crown, else fine in wrappers. Bartok won the National Book Critics Circle Award for her memoir The Memory Palace. Uncommon as an advance copy, and especially so signed.

[#034438]

SOLD

NY, Atheneum, 1975. Inscribed by Konigsburg to Frog and Toad author Arnold Lobel, "whose work I have long admired for its important wild element and whose person I came to admire in mid-March in Mississippi." Konigsburg was a two-time Newbery Medal winner, for From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler in 1967, and for The View from Saturday, 29 years later. Lobel, whose work includes numerous Newbery Honor books and a Caldecott Medal winner, was a speaker, along with Konigsburg, at the Children's Book Festival at the University of Southern Mississippi in March, 1976, the month of this inscription. The title of this book was later corrected to The Second Mrs. Gioconda, i.e., Mona Lisa. A wonderful association copy linking two writers in the pantheon of children's literature. Trace edge foxing; near fine in a very near fine dust jacket.

[#034450]

SOLD

NY, Atheneum, 1975. Inscribed by Konigsburg to Frog and Toad author Arnold Lobel, "whose work I have long admired for its important wild element and whose person I came to admire in mid-March in Mississippi." Konigsburg was a two-time Newbery Medal winner, for From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler in 1967, and for The View from Saturday, 29 years later. Lobel, whose work includes numerous Newbery Honor books and a Caldecott Medal winner, was a speaker, along with Konigsburg, at the Children's Book Festival at the University of Southern Mississippi in March, 1976, the month of this inscription. The title of this book was later corrected to The Second Mrs. Gioconda, i.e., Mona Lisa. A wonderful association copy linking two writers in the pantheon of children's literature. Trace edge foxing; near fine in a very near fine dust jacket.

[#034450]

SOLD

Garden City, Doubleday Doran, 1928. Inscribed by the author at Christmas in the year of publication: "To Somebody the Kewpies love/ from all the band, including Dr. Goldwater and Rose O'Neill." Creator of the Kewpie comic strip, and the inventor of the Kewpie doll, O'Neill was also the first published female cartoonist in the U.S. and active in the women's suffrage movement. Small (original) price stamp rear flyleaf, slight play in text block, and light crown wear; a very good copy in a good, edge-chipped dust jacket with some tearing at mid-spine. With a letter of provenance from a descendant of Dr. Goldwater. Uncommon signed and in dust jacket.

[#033649]

$1,500

Garden City, Doubleday Doran, 1928. Inscribed by the author at Christmas in the year of publication: "To Somebody the Kewpies love/ from all the band, including Dr. Goldwater and Rose O'Neill." Creator of the Kewpie comic strip, and the inventor of the Kewpie doll, O'Neill was also the first published female cartoonist in the U.S. and active in the women's suffrage movement. Small (original) price stamp rear flyleaf, slight play in text block, and light crown wear; a very good copy in a good, edge-chipped dust jacket with some tearing at mid-spine. With a letter of provenance from a descendant of Dr. Goldwater. Uncommon signed and in dust jacket.

[#033649]

$1,500

NY, Hill and Wang, (2008). Inscribed by Broecker, the geoscientist whose 1975 paper "Climactic Change: Are We On the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?" popularized the term "global warming" and sounded an early (unheeded) alarm. Broecker has been called "one of the founding fathers of climate science" and "the world's expert on climate history." Fine in a fine, price-clipped dust jacket.

[#033867]

SOLD

NY, Hill and Wang, (2008). Inscribed by Broecker, the geoscientist whose 1975 paper "Climactic Change: Are We On the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?" popularized the term "global warming" and sounded an early (unheeded) alarm. Broecker has been called "one of the founding fathers of climate science" and "the world's expert on climate history." Fine in a fine, price-clipped dust jacket.

[#033867]

SOLD

NY, Norton, (2008). The advance reading copy of the revised and expanded edition (following Plan B and Plan B 2.0 in 2003 and 2006, respectively). This copy has a sticky note tipped in on which Brown has inscribed the book to Peter [Matthiessen] in 2007, prior to publication: "Hi Peter/ Thought you might like an advance copy/ Cheers/ Les Brown." With Peter Matthiessen's underlinings and notations in the preface and the first chapter. By this time, Matthiessen himself had been publicizing climate change for a half century: his book Wildlife in America was published in 1959. Well-worn, with dampstained upper corners. A good copy in wrappers.

[#032459]

SOLD

NY, Norton, (2008). The advance reading copy of the revised and expanded edition (following Plan B and Plan B 2.0 in 2003 and 2006, respectively). This copy has a sticky note tipped in on which Brown has inscribed the book to Peter [Matthiessen] in 2007, prior to publication: "Hi Peter/ Thought you might like an advance copy/ Cheers/ Les Brown." With Peter Matthiessen's underlinings and notations in the preface and the first chapter. By this time, Matthiessen himself had been publicizing climate change for a half century: his book Wildlife in America was published in 1959. Well-worn, with dampstained upper corners. A good copy in wrappers.

[#032459]

SOLD

Jackson Hole, Rink House, (2013). His first book, examining the 8,000 year old sport of skiing, "the miracle of snow," the possible demise of both in the current century, and the efforts underway to repair "the water cycle." Signed by the author. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with a blurb by Bill McKibben on the rear panel: "Skiing offers a good barometer of the trouble we're in..."

[#033866]

SOLD

Jackson Hole, Rink House, (2013). His first book, examining the 8,000 year old sport of skiing, "the miracle of snow," the possible demise of both in the current century, and the efforts underway to repair "the water cycle." Signed by the author. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with a blurb by Bill McKibben on the rear panel: "Skiing offers a good barometer of the trouble we're in..."

[#033866]

SOLD

Chicago, University of Chicago Press, (2016). Inscribed by the author in the year of publication. The Indian novelist explores our failure to act on climate change as being primarily a failure of imagination: Ghosh posits that fiction is the medium best suited for comprehending the scale and violence of climate change, before ultimately grappling with the subject as a society. Fine in a fine dust jacket.

[#033610]

SOLD

Chicago, University of Chicago Press, (2016). Inscribed by the author in the year of publication. The Indian novelist explores our failure to act on climate change as being primarily a failure of imagination: Ghosh posits that fiction is the medium best suited for comprehending the scale and violence of climate change, before ultimately grappling with the subject as a society. Fine in a fine dust jacket.

[#033610]

SOLD

(NY), Bloomsbury, (2006). An early entry in the now ongoing deluge of books on climate change, this book grew out of Kolbert's three-part New Yorker essay on the subject, written at a time when it was still believed that sounding the alarm would lead to action. Signed by the author. Fine but for a turned page corner, in a near fine, mildly toned dust jacket. Advance praise: "Reading Field Notes from a Catastrophe during the 2005 hurricane season is what it must have been like to read Silent Spring forty years ago." Uncommon signed.

[#033606]

SOLD

(NY), Bloomsbury, (2006). An early entry in the now ongoing deluge of books on climate change, this book grew out of Kolbert's three-part New Yorker essay on the subject, written at a time when it was still believed that sounding the alarm would lead to action. Signed by the author. Fine but for a turned page corner, in a near fine, mildly toned dust jacket. Advance praise: "Reading Field Notes from a Catastrophe during the 2005 hurricane season is what it must have been like to read Silent Spring forty years ago." Uncommon signed.

[#033606]

SOLD

Washington DC, National Geographic, (2008). The first American edition and apparently the first hardcover edition. Inscribed by the author. The six main chapters of the book describe the planet as it continues to warm, one degree Celsius per chapter: an act of research by Lynas rather than imagination, where possible. Fine in a fine dust jacket.

[#033607]

SOLD

Washington DC, National Geographic, (2008). The first American edition and apparently the first hardcover edition. Inscribed by the author. The six main chapters of the book describe the planet as it continues to warm, one degree Celsius per chapter: an act of research by Lynas rather than imagination, where possible. Fine in a fine dust jacket.

[#033607]

SOLD

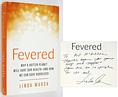

(NY), Rodale, (2013). Marsa delineates the medical meltdowns that will accompany climate change. This is a review copy, inscribed by the author to Bill McKibben, on the day of publication: "Thanks again for your help and support. You are an inspiration to us all." McKibben has provided a blurb for the rear panel. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with the publisher's press release laid in. A notable association copy.

[#033881]

SOLD

(NY), Rodale, (2013). Marsa delineates the medical meltdowns that will accompany climate change. This is a review copy, inscribed by the author to Bill McKibben, on the day of publication: "Thanks again for your help and support. You are an inspiration to us all." McKibben has provided a blurb for the rear panel. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with the publisher's press release laid in. A notable association copy.

[#033881]

SOLD

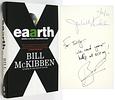

NY, Henry Holt/Times Books, (2010). Twenty years after the warnings in his book The End of Nature went unheeded, McKibben writes about our current best responses to the ensuing tragedy. Inscribed by McKibben to a fellow activist: "For _______, We need your help at 350.org!/ Bill." 350.org is the organization founded by McKibben with the goal of reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to 350ppm. With the recipient's ownership signature dated in the month of publication. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with blurbs by Rebecca Solnit, Barbara Kingsolver, Alan Weisman, Tim Flannery, and James E. Hansen. The spelling of the title (the extra "a" in Earth) is meant to reflect a small yet fundamental change in the planet.

[#033608]

SOLD

NY, Henry Holt/Times Books, (2010). Twenty years after the warnings in his book The End of Nature went unheeded, McKibben writes about our current best responses to the ensuing tragedy. Inscribed by McKibben to a fellow activist: "For _______, We need your help at 350.org!/ Bill." 350.org is the organization founded by McKibben with the goal of reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to 350ppm. With the recipient's ownership signature dated in the month of publication. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with blurbs by Rebecca Solnit, Barbara Kingsolver, Alan Weisman, Tim Flannery, and James E. Hansen. The spelling of the title (the extra "a" in Earth) is meant to reflect a small yet fundamental change in the planet.

[#033608]

SOLD

NY, Bloomsbury, (2010). The story of how a small number of politically and industry-connected scientists caused doubt, denial and delay on issues of global warming, acid rain, the ozone hole, DDT, and tobacco, deliberately misleading the public and the government, and obscuring the truth. Inscribed by Oreskes. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with a flyer for a workshop and book signing laid in.

[#033905]

SOLD

NY, Bloomsbury, (2010). The story of how a small number of politically and industry-connected scientists caused doubt, denial and delay on issues of global warming, acid rain, the ozone hole, DDT, and tobacco, deliberately misleading the public and the government, and obscuring the truth. Inscribed by Oreskes. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with a flyer for a workshop and book signing laid in.

[#033905]

SOLD

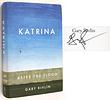

NY, Simon & Schuster, (2015). Written ten years after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, Rivlin's book does not push the link between climate change and hurricanes, but does describe a possible future by way of examining the recent past: Katrina was just a part of the record-breaking hurricane season of 2005. Signed by the author. Additional, partial, gift inscription on the front flyleaf; minor corner taps. Near fine in a near fine dust jacket with a small ink mark on the front panel. Uncommon signed.

[#033609]

SOLD

NY, Simon & Schuster, (2015). Written ten years after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, Rivlin's book does not push the link between climate change and hurricanes, but does describe a possible future by way of examining the recent past: Katrina was just a part of the record-breaking hurricane season of 2005. Signed by the author. Additional, partial, gift inscription on the front flyleaf; minor corner taps. Near fine in a near fine dust jacket with a small ink mark on the front panel. Uncommon signed.

[#033609]

SOLD

NY, North Point Press, (2004). A report from the front lines of global warming, in Alaska, 15 years ago. Signed by the author. One very light corner tap; else fine in a fine dust jacket. Uncommon signed.

[#033886]

SOLD

NY, North Point Press, (2004). A report from the front lines of global warming, in Alaska, 15 years ago. Signed by the author. One very light corner tap; else fine in a fine dust jacket. Uncommon signed.

[#033886]

SOLD

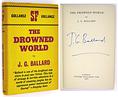

London, Gollancz, 1962. The uncorrected proof copy of Ballard's second book, which he later called his "first novel" after disavowing The Wind From Nowhere as "a piece of hackwork." Signed on the title page by Ballard. In this novel, global warming has rendered most of Earth uninhabitable, making The Drowned World not only one of the great works of dystopian fiction, but one of the earliest works of climate fiction. Tapebound, in unprinted wrappers; spine slant to text block; near fine in a near fine, mildly spine- and edge-tanned proof dust jacket with a "0/0" price on the front flap. Scarce: we have never seen another proof copy of this, nor any earlier Ballard proof (i.e., of The Wind From Nowhere), and can find no indication of institutional holdings in OCLC, nor any auction records for a proof copy. A rare, perhaps at this point, unique, state of a seminal novel in a genre that is only now melding into the field of mainstream literature, outside of the genre of speculative science fiction.

[#033324]

SOLD

London, Gollancz, 1962. The uncorrected proof copy of Ballard's second book, which he later called his "first novel" after disavowing The Wind From Nowhere as "a piece of hackwork." Signed on the title page by Ballard. In this novel, global warming has rendered most of Earth uninhabitable, making The Drowned World not only one of the great works of dystopian fiction, but one of the earliest works of climate fiction. Tapebound, in unprinted wrappers; spine slant to text block; near fine in a near fine, mildly spine- and edge-tanned proof dust jacket with a "0/0" price on the front flap. Scarce: we have never seen another proof copy of this, nor any earlier Ballard proof (i.e., of The Wind From Nowhere), and can find no indication of institutional holdings in OCLC, nor any auction records for a proof copy. A rare, perhaps at this point, unique, state of a seminal novel in a genre that is only now melding into the field of mainstream literature, outside of the genre of speculative science fiction.

[#033324]

SOLD

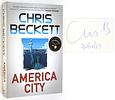

(London), Corvus, (2017). Signed by the author in the month prior to publication. The British scifi author takes on a future America where droughts, hurricanes, and floods have created a humanitarian crisis at the border between northern and southern states, and the politicians find a way to blame Canada. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with a label indicating the book is a "BBC Radio 2 Book Club" selection. Beckett's Eden trilogy was highly praised, and the author -- who is also a sociologist -- is well-regarded for using the science fiction genre as a way to explore social, political, and theological issues.

[#033880]

SOLD

(London), Corvus, (2017). Signed by the author in the month prior to publication. The British scifi author takes on a future America where droughts, hurricanes, and floods have created a humanitarian crisis at the border between northern and southern states, and the politicians find a way to blame Canada. Fine in a fine dust jacket, with a label indicating the book is a "BBC Radio 2 Book Club" selection. Beckett's Eden trilogy was highly praised, and the author -- who is also a sociologist -- is well-regarded for using the science fiction genre as a way to explore social, political, and theological issues.

[#033880]

SOLD

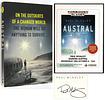

London, Gollancz, (2017). The advance reading copy of McAuley's science fiction novel of a genetically-edited woman hiding out with a hostage in the newly established Antarctic Peninsula, in a world where the climate has changed dramatically faster than the politics of power, ethnicity or gender. Signed by McAuley. Fine in wrappers, with an announcement for the book signing laid in.

[#033888]

$100

London, Gollancz, (2017). The advance reading copy of McAuley's science fiction novel of a genetically-edited woman hiding out with a hostage in the newly established Antarctic Peninsula, in a world where the climate has changed dramatically faster than the politics of power, ethnicity or gender. Signed by McAuley. Fine in wrappers, with an announcement for the book signing laid in.

[#033888]

$100

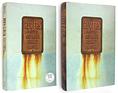

NY, Simon & Schuster, (2013). Two volumes: both a first edition, inscribed by the author and the advance reading copy of this novel that posits an unending series of major hurricanes resulting in the southern portion of the U.S., along the Gulf of Mexico, being abandoned by the U.S. government. The Category 5 hurricanes that hit the Caribbean in close succession in 2017 gave this fictional premise a reality that its author probably never conceived during the writing of this novel. The advance copy is very near fine in wrappers; the book and jacket have a tiny tear at the spine crown, else fine in a fine dust jacket. Both volumes carry advance praise from James Lee Burke.

[#033613]

SOLD

NY, Simon & Schuster, (2013). Two volumes: both a first edition, inscribed by the author and the advance reading copy of this novel that posits an unending series of major hurricanes resulting in the southern portion of the U.S., along the Gulf of Mexico, being abandoned by the U.S. government. The Category 5 hurricanes that hit the Caribbean in close succession in 2017 gave this fictional premise a reality that its author probably never conceived during the writing of this novel. The advance copy is very near fine in wrappers; the book and jacket have a tiny tear at the spine crown, else fine in a fine dust jacket. Both volumes carry advance praise from James Lee Burke.

[#033613]

SOLD

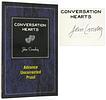

(Burton), Subterranean, 2008. The advance reading copy of these two intertwined stories, one that takes place on Earth, the other a children's story that takes place on another planet. Signed by the author. Crowley is one of our most highly regarded fantasy writers, having won the World Fantasy Award for a novel, Little, Big in 1982; a novella, "Great Work of Time," in 1990; and for Life Achievement, in 2006. Minor cover splaying; near fine in wrappers. Scarce in this advance issue, especially signed.

[#033925]

$175

(Burton), Subterranean, 2008. The advance reading copy of these two intertwined stories, one that takes place on Earth, the other a children's story that takes place on another planet. Signed by the author. Crowley is one of our most highly regarded fantasy writers, having won the World Fantasy Award for a novel, Little, Big in 1982; a novella, "Great Work of Time," in 1990; and for Life Achievement, in 2006. Minor cover splaying; near fine in wrappers. Scarce in this advance issue, especially signed.

[#033925]

$175

Charleston, The Parchment Gallery, (n.d.). A limited edition print of a Cummings' drawing, this being Copy No. 8 of 100 copies, likely printed on the occasion of a posthumous exhibit of Cummings' artwork, curated by William Plumley. An undated newspaper clipping about the show accompanies the piece, reprinted as a promotional flyer for the gallery holding the exhibition. According to the newspaper piece, this was the first show of Cummings' work after his artwork had been given to the Gotham Book Mart in 1968 for exhibition and sales purposes. In this image, Cummings is seated on a park bench, holding a single flower (tulip?). Printed in brown, on parchment, now sunned. 11" x 15", although the lower edge is chipped approximately 1/8". Additional small closed edge tears; overall about very good. This is the only limited edition print of a Cummings artwork we've encountered, and issued on a notable occasion -- the first posthumous showing of his artwork outside of the Gotham Book Mart's own gallery.

[#034443]

SOLD

Charleston, The Parchment Gallery, (n.d.). A limited edition print of a Cummings' drawing, this being Copy No. 8 of 100 copies, likely printed on the occasion of a posthumous exhibit of Cummings' artwork, curated by William Plumley. An undated newspaper clipping about the show accompanies the piece, reprinted as a promotional flyer for the gallery holding the exhibition. According to the newspaper piece, this was the first show of Cummings' work after his artwork had been given to the Gotham Book Mart in 1968 for exhibition and sales purposes. In this image, Cummings is seated on a park bench, holding a single flower (tulip?). Printed in brown, on parchment, now sunned. 11" x 15", although the lower edge is chipped approximately 1/8". Additional small closed edge tears; overall about very good. This is the only limited edition print of a Cummings artwork we've encountered, and issued on a notable occasion -- the first posthumous showing of his artwork outside of the Gotham Book Mart's own gallery.

[#034443]

SOLD

ca. 1928.

ca. 1928. A large portrait by Cummings of his stepdaughter, Diana Barton, with one of her dogs at Joy Farm in New Hampshire, sometime between 1927 and 1930. Diana was born in 1921; Cummings met Anne Barton in 1925 and they spent several summers at Joy Farm beginning in 1927. Diana is standing outside, with her dog at her side and Mount Chocorua in the background.

One of the best-loved American poets of the 20th century, Cummings was also a prolific visual artist: he considered writing and painting to be his "twin obsessions." He exhibited his work in the annual Society of Independent Artists shows from 1916-1927, and he was the art editor of The Dial magazine, the preeminent Modernist literary journal in the U.S., in the 1920s. In 1933, Cummings published a book of his artwork in a limited edition. Called CIOPW, it took its title from the media he used in his art: charcoal, ink, oil, pencil and watercolors. In his early years he emphasized abstract painting; from the 1930s on he tended toward representational images, albeit with a range of inventive palettes, which some have compared to his inventiveness with words and poetic forms and structures.

This is an early, transitional image by Cummings, painted as he was moving from abstract to representational art but still using the brilliant color schemes and flourishes that link his later art back to his abstracts. In this painting, the sky is "psychedelic," the mountain range has a variety and richness of color, and Cummings has taken liberties with the proportions. 35-3/4" x 47-3/4". Oil on Upson Processed Board (a fiberboard used as a building material in the early 20th century), with a narrow (2" x 8") chip missing from the lower left corner, affecting only flora. "DIANA BARTON" written on the back (in a child's hand?); also "1928-9?" Unsigned, as was most of Cummings' artwork, as he adhered to the theory (popularized decades later) that art is best encountered independent of its artist, even as his paintings seem to shed light on his innovative, visual style of poetry.

[#033852] $15,000 (Port Townsend), Copper Canyon Press, 1982. The hardcover issue. Inscribed by the author in the year of publication: "For Andy -- with all the prayers I know, and, if need be, in tongues. Love, Madeline/ 12-18-82/ Amherst." The award-winning author spent nearly 40 years as a Catholic nun, and her inscription presumably alludes to that history. Light foxing to the edges of the text block and boards; near fine in a near fine dust jacket.

[#033902]

SOLD

(Port Townsend), Copper Canyon Press, 1982. The hardcover issue. Inscribed by the author in the year of publication: "For Andy -- with all the prayers I know, and, if need be, in tongues. Love, Madeline/ 12-18-82/ Amherst." The award-winning author spent nearly 40 years as a Catholic nun, and her inscription presumably alludes to that history. Light foxing to the edges of the text block and boards; near fine in a near fine dust jacket.

[#033902]

SOLD