Signed vs. Inscribed

One of the questions I've been asked most often in recent years is "Which is better -- having a book just signed by the author or having it inscribed?" In general my answer has been that the more writing by the author in a book, the better. And most especially, I've encouraged collectors when getting their own books signed to have them personally inscribed by the author.

I know I'm bucking the current trend on this issue, but I continue to do so, and I think I'm right. Here's why.

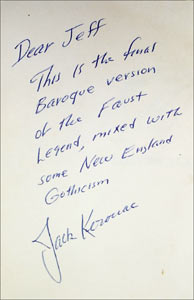

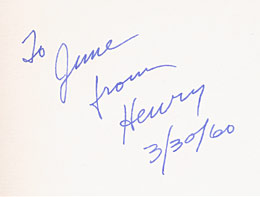

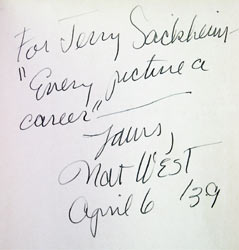

For a long time -- generations, literally -- there was a clearly established hierarchy of values that pertained to books signed by their authors. The best copy was the dedication copy, and usually there was only one of these. Next best were association copies, that is, books inscribed by the author to someone notable or important in the author's life -- a relative, a friend, a mentor, another writer. After that were "presentation copies," which simply meant those books inscribed by the author to someone who was not important to the author, or whose importance was unknown. And finally, at the bottom of the hierarchy, were books that were just signed, with no further inscription, no other writing, etc.

In recent years, for reasons that most people don't know about or are unable to articulate, the last two kinds of signed books have appeared to switch places in the hierarchy, with there being a preference in the marketplace for books that were just signed, rather than having been inscribed. I believe this preference, which flies in the face of longstanding tradition in the book collecting world, has a specific historical origin and that the seeming consensus in the marketplace reflects a backlash against specific practices by certain individuals which, in the fog of time, has come to look like a rational rethinking of the old priorities and a new philosophy toward signed books. The fact that we have mostly forgotten the historical reasons for this preference arising means that, for the most part, it is a preference based more on received wisdom than on careful, thoughtful consideration. And I believe that, as a result of its relatively thin basis in rational consideration, this preference is beginning to lose its hold in the marketplace and the old hierarchy will again, in time, reassert itself -- and probably soon.

The story begins in the late 1970s and goes into the early 1980s. At the time, the hierarchy in signed books was as I listed it above, and as it had been for generations: dedication copy, association copy, presentation copy, signed copy. The logic of such a hierarchy was more or less self-evident. The dedication copy is usually unique or, at most, limited to a couple of copies -- inscribed by the author to the person he or she thought important enough to dedicate the book to, in print. Association copies that clearly involved significant figures in the author's life or in the general cultural life of which the author was a part also have an obvious, self-evident value although not one as unique or specific as the dedication copy. Presentation copies were more ambiguous, but the mere fact that a presentation copy could sometimes, with a little bit of research, luck, or specialized knowledge "become" an association copy argued for their importance, and the closeness of the two in the hierarchy. Signed books were last, and there was even the suggestion of a "taint" to them -- as though perhaps the only justification for a book having been simply autographed was a kind of celebrity worship that somehow was a bit inappropriate to the book world.

Because this preference was so clear and longstanding in the book collecting world, dealers preferred to have presentation copies over just plain signed copies, collectors preferred them, and there was a premium placed on their price in the market place.

Thus, one enterprising bookselling firm in the New York area, recognizing this preference, decided to exploit it -- and do so relentlessly. New York is a place where, even before the days of routine author tours upon publication of a new book, there were readings every day, as well as lectures, talks, and seminars with well-known authors that were open to the public. Sometimes there would be several in a single day. The firm I'm referring to was a family business and they would attend these readings and talks en masse -- four or five or sometimes even more family members, each of them carrying a bag full of the author's first editions, and each one asking the author to inscribe the books to them personally. Then, when they issued catalogs, nearly every book was listed as a "signed presentation copy inscribed by the author" -- a most desirable designation, especially for modern first editions, many of which are not inherently rare unless there is something special about a particular copy.

This went on for a few years, and the family grew bolder, branching out its operation so that they could reach more authors than just the ones who showed up at readings in New York. One began to hear stories passed around among writers, each of whom had received identically worded, ingratiating letters from a correspondent claiming to be the author's greatest fan, and sending along a box of books to be inscribed personally and sent back. Then, some writers began noticing that the "fan" would write a follow-up letter some months later, sending along another batch of books to be inscribed -- often including copies of titles the author remembered signing in the earlier batch. Clearly there was something fishy here. Authors began to dislike it, feel manipulated, deceived and exploited. Several began to look askance at booksellers in general, and at signing books at all. Booksellers, of course, recognized it for exactly what it was and after a time books inscribed to these family members began to seem like the products of a fraud, whereas a plain signed book carried no such taint. And collectors began to absorb the preference that booksellers were beginning to show, although for the most part they did not know the reason and did not realize that it was only books that were inscribed to these particular half dozen or so individuals that were "tainted." The perception grew that somehow all inscribed books were tainted or at least less desirable than books that were just signed.

This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: if collectors feel that books that are inscribed are less valuable than books that are just signed -- for whatever reason -- it will be harder to sell books that are inscribed than books that are signed. And that will "prove" that books that are inscribed are less saleable and less valuable. Etc.

But such a view not only defies long-established historical precedent, it also diminishes and demeans collecting, and collectors today. For not only can a presentation copy to an unknown third party "turn into" an association copy after a little research, but a collector's own copy can become an association copy if the collector stays with it long enough and seriously enough for the collection to become recognizably important. Hemingway's first bibliographer was Louis Cohen, a fan and book collector. A Hemingway book inscribed to Cohen would, at the time, have been a simple presentation copy to a person of no particular consequence. Today it would be viewed as a highly desirable association copy. Similarly, if Carl Peterson had ever managed to get Faulkner to inscribe a book to him, it would now be viewed as a major association copy. And the time-honored practice of identifying books from an important collection -- "the Doheny copy" or "the Bradley Martin copy," for example -- underscores that collectors themselves can become significant figures.

Perhaps most telling in terms of the underlying values behind these questions is that in the cases of long-dead authors like Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Joyce, it has always been true that a presentation copy has had a higher value in the marketplace than one that was just signed. They are more interesting, they can provoke interesting questions that lead to discovery -- one of the pleasures of collecting -- and "the more writing by the author in the book, the better" has been, and still is, a generally accepted truth in this part of the market. Since we don't know who the next generation of Faulkners and Hemingways might be -- but we do know there will be one -- is there any reason that different criteria should apply to the inscriptions of contemporary authors than to "classic" ones? I don't think so.

When you buy a signed book you are purchasing a signature, but when you buy an inscribed book you are getting a story. We recently bought a collection of Paul Bowles books, all of them inscribed to one person, someone whom we had never heard of. But the story behind the books was fascinating: when Bowles came to the U.S. To be treated for health problems he arranged to stay with a longtime friend, a writer who had been close to Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers, among others. However, she lived on an upper floor of her apartment complex and Bowles could not navigate the stairways leading to her place: she arranged for him to stay with a friend of hers -- an administrator at a local college and a longtime fan, and collector, of Paul Bowles's writing -- who lived on a lower floor of the same complex. Bowles stayed there while he underwent his treatments, and he inscribed of all her books to her. Had she merely had him sign them, in deference to the current fashion and prevailing "wisdom" in the marketplace, they would have ended up being batch of nondescript signed books. But since she had them inscribed, they are now identifiable as being from a particular time in Bowles's life, and she herself becomes a character, albeit a minor one, in his biography. Anyone purchasing one of these books is recognizing, even participating in, a small but critical moment in the life of a major author, and his or her Bowles collection is the richer for it.

Almost simultaneous with the apparent switch in priorities

regarding signed vs. inscribed, there has also been a huge run-up in

the prices of fine copies of notable "high spots." Part

of this is attributable to the large number of people who have

entered this market since the advent of the Internet made more books

more widely available than ever before and made price comparison so

much easier that the "learning curve" for getting into

the market with confidence appeared to be shortened dramatically.

Fine copies of first editions of extremely well-known and collectible

books like To Kill a Mockingbird

and The Catcher in the Rye consequently went from $3000

to $6000 to $12-15000 to as much as $35000 in a couple of blinks of

an eye. Close-to-fine copies, including copies in attractive but

"restored" dust jackets, followed in their wake. In the

meantime, signed copies of collectible but less "obvious"

first editions have increased in value at a slower, more steady pace.

And the recent preference for signed over inscribed copies has meant

that inscribed copies -- including association copies --

have risen in value even more slowly. This is a trend that I believe

is likely to be short-lived: while it has always been true that

"condition, condition, condition" has been the most

critical criterion in determining the collectibility of modern books,

what fine condition does is set a particular copy apart from others

as part of a much smaller subset of the available copies of that

title. Signatures do the same thing; inscriptions even more so; and

association copies are truly a tiny subset of the overall number of

copies of any given title. Yet at the moment, "fine condition"

commands a much higher premium in the first edition world than a fine

association, and my guess is that this preference will not only even

out over time but will in fact reverse itself, as the rarity of good

presentations and good associations becomes increasingly more evident

while at the same time the notion of "fine condition"

becomes increasingly diluted by the proliferation of restored dust

jackets. This moment seems to me to be a particularly good time to

collect association copies, and even presentation copies, as both

seem to be relatively undervalued compared to merely signed copies or

even unsigned copies in fine condition. I wouldn't be surprised

to look back in five years on the catalogs we're receiving

today and be astonished at how low the prices of good presentation

copies and association copies were "in those days." The

first edition marketplace has been in flux for several years for a

number of reasons. Now it seems to me to be headed in the direction

of being a more "mature" and stable market than it has

been for a while, and that means, in part, a market that is returning

to the longstanding tradition valuing an author's original

writing, and the more of it, the better.

have risen in value even more slowly. This is a trend that I believe

is likely to be short-lived: while it has always been true that

"condition, condition, condition" has been the most

critical criterion in determining the collectibility of modern books,

what fine condition does is set a particular copy apart from others

as part of a much smaller subset of the available copies of that

title. Signatures do the same thing; inscriptions even more so; and

association copies are truly a tiny subset of the overall number of

copies of any given title. Yet at the moment, "fine condition"

commands a much higher premium in the first edition world than a fine

association, and my guess is that this preference will not only even

out over time but will in fact reverse itself, as the rarity of good

presentations and good associations becomes increasingly more evident

while at the same time the notion of "fine condition"

becomes increasingly diluted by the proliferation of restored dust

jackets. This moment seems to me to be a particularly good time to

collect association copies, and even presentation copies, as both

seem to be relatively undervalued compared to merely signed copies or

even unsigned copies in fine condition. I wouldn't be surprised

to look back in five years on the catalogs we're receiving

today and be astonished at how low the prices of good presentation

copies and association copies were "in those days." The

first edition marketplace has been in flux for several years for a

number of reasons. Now it seems to me to be headed in the direction

of being a more "mature" and stable market than it has

been for a while, and that means, in part, a market that is returning

to the longstanding tradition valuing an author's original

writing, and the more of it, the better.

Copyright © 2002 by Ken Lopez