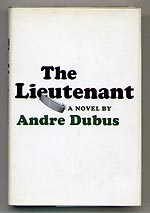

Introduction to Our Catalog of Authors' Firsts

My first book was a novel, bought by Dial Press when I

was twenty-nine, and published when I was thirty. If I were

a young writer now, thirty years later, that book would not

be published. My first book would be the collection of

stories that was my second book, published when I was

thirty-nine, in 1975, by David R. Godine, a small publisher.

In 1975 Mark Smith, the novelist, told me that the average

age of the writer of a first novel or book of stories would

from then on be thirty-nine. He said publishers used to buy

a writer's talent, hoping that the writer's fourth or fifth

book would sell enough copies to earn money. He said: Now

they want the money with the first book. When Dial bought

my novel, they were doing what publishers used to do: paying

a small advance, printing a small number of books, and

waiting for me to grow, or my readers to multiply. They did

not want my second book, because it was a collection of

stories, and years later, with gratitude, I found David

Godine.

My first book was a novel, bought by Dial Press when I

was twenty-nine, and published when I was thirty. If I were

a young writer now, thirty years later, that book would not

be published. My first book would be the collection of

stories that was my second book, published when I was

thirty-nine, in 1975, by David R. Godine, a small publisher.

In 1975 Mark Smith, the novelist, told me that the average

age of the writer of a first novel or book of stories would

from then on be thirty-nine. He said publishers used to buy

a writer's talent, hoping that the writer's fourth or fifth

book would sell enough copies to earn money. He said: Now

they want the money with the first book. When Dial bought

my novel, they were doing what publishers used to do: paying

a small advance, printing a small number of books, and

waiting for me to grow, or my readers to multiply. They did

not want my second book, because it was a collection of

stories, and years later, with gratitude, I found David

Godine.

I am writing this over twenty years after Mark Smith's prediction. In this decade I have read manuscripts of good novels and collections of stories that New York publishers have rejected. These rejections are not the sort that should dishearten a writer; in essence, they have said: I like this book, but don't know how to sell it. One day a couple of years ago, my concern shifted for a few moments from writers to editors, and I phoned my agent and told him there must be a lot of frustrated editors too. He said: Of course there are; an editor wants to buy a book and he shows it to the managing editor who calls someone at the bookstore chains, a guy who was selling cars six months ago and thinks of a book as a unit, and that guy says We won't sell it, and the editor has to reject it. I do not know if Mark Smith was thinking about bookstore chains in 1975; nor do I know if the chains existed then, or if now they are the major reason for large publishing houses' treatment of first books. But I do know that it is much harder now to publish a first book than it has ever been in my adult life, and I believe the small publishers, always important as the homes of poets, are more important, offering more hope, than ever before.

A first book is a treasure, and all these truths and

quasi-truths I have written about publishing are finally

ephemeral. An older writer knows what a younger one has not

yet learned. What is demanding and fulfilling is writing a

single word, trying to write le mot juste, as

Flaubert said; writing several of them which becomes a

sentence. When a writer does that, day after day, working

alone with little encouragement, often with discouragement

flowing in the writer's own blood, and with the occasional

rush of excitement that empties oneself, so that the self is

for minutes or longer in harmony with eternal astonishments

and visions of truth, right there on the page on the desk;

and when a writer does this work steadily enough to complete

a manuscript long enough to be a book, the treasure is on

the desk. If the manuscript itself, mailed out to the world

where other truths prevail, is never published, the writer

will suffer bitterness, sorrow, anger, and, more

dangerously, despair, convinced that the work was not

worthy, so not worth those days at the desk. But the writer

who endures and keeps working will finally know that writing

the book was something hard and glorious, for at the desk a

writer must try to be free of prejudice, meanness of spirit,

pettiness, and hatred; strive to be a better human being

than the writer normally is, and to do this through

concentration on a single word, and then another, and

another. This is splendid work, as worthy and demanding as

any, and the will and resilience to do it are good for the

writer's soul. If the work is not published, or is

published for little money and less public attention, it

remains a spiritual, mental, and physical achievement; and

if, in public, it is the widow's mite, it is also, like the

widow, more blessed.

A first book is a treasure, and all these truths and

quasi-truths I have written about publishing are finally

ephemeral. An older writer knows what a younger one has not

yet learned. What is demanding and fulfilling is writing a

single word, trying to write le mot juste, as

Flaubert said; writing several of them which becomes a

sentence. When a writer does that, day after day, working

alone with little encouragement, often with discouragement

flowing in the writer's own blood, and with the occasional

rush of excitement that empties oneself, so that the self is

for minutes or longer in harmony with eternal astonishments

and visions of truth, right there on the page on the desk;

and when a writer does this work steadily enough to complete

a manuscript long enough to be a book, the treasure is on

the desk. If the manuscript itself, mailed out to the world

where other truths prevail, is never published, the writer

will suffer bitterness, sorrow, anger, and, more

dangerously, despair, convinced that the work was not

worthy, so not worth those days at the desk. But the writer

who endures and keeps working will finally know that writing

the book was something hard and glorious, for at the desk a

writer must try to be free of prejudice, meanness of spirit,

pettiness, and hatred; strive to be a better human being

than the writer normally is, and to do this through

concentration on a single word, and then another, and

another. This is splendid work, as worthy and demanding as

any, and the will and resilience to do it are good for the

writer's soul. If the work is not published, or is

published for little money and less public attention, it

remains a spiritual, mental, and physical achievement; and

if, in public, it is the widow's mite, it is also, like the

widow, more blessed.

January, 1997

Copyright © 1997 by Andre Dubus